Written in 2011 and updated in 2014 by Tom Tremaine 1

Edited in 2017 by Stacey Lara, Director, Parent Advocacy Project, Native American Law Center, University of Washington Law School, Native American Law Center. 2017.

2016 ICWA Update

On June 8, 2016, the Bureau for Indian Affairs (BIA) released the Final Rule on the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), the major federal law that protects American Indian and Alaska Native children who come to the attention of the child welfare system and helps them stay connected to their families, cultures and communities. These regulations are the first set of substantive regulations guiding the implementation of ICWA since the law’s passage in 1978.

The final regulations are intended to provide clarity and certainty in interpreting the law in a way that is consistent with Congress’s intent and other existing federal child welfare laws. The regulations are intended to also provide consistency in the implementation of ICWA across all states. Further, the final regulations clarify the efforts needed to search for placements for American Indian and Alaska Native children coming in contact with the child welfare system with family members, both Indian and non-Indian.

The new regulations are effective 180 days following the June 8, 2016 publication date.

Please see the following hyperlinks for additional information on the new ICWA regulations:

- Final Rule: ICWA

- BIA Press Release

- FAQs on the Final Rule

- Letter Sent to State Governors

- Letter Sent to Tribal Leaders

The original federal guidelines on ICWA operated for over 36 years, but fell short of the guidance public and private agencies and state courts needed to provide uniform implementation of the law and provide much needed protections to American Indian and Alaska Native children. In response to these challenges with implementing ICWA, the BIA published on February 25, 2015, ICWA Guidelines for state courts and agencies that took effect immediately. These Guidelines superseded and replaced the 1979 Guidelines and expand their application from just state courts to state courts and child welfare agencies. Unlike regulations, guidelines are advisory only and not binding.

Chapter Sections

§1 Purpose Statement

The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA) is federal legislation that imposes jurisdictional, procedural, and evidentiary standards on state courts in “child custody proceedings” involving “Indian children.” The purposes of the ICWA are (1) to protect Indian children from unwarranted removal from their families; (2) when such removal is warranted and necessary, ensure placement of Indian children in homes that will reflect the unique values of Indian culture; and (3) promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families.2

In the 39 years since its enactment, the ICWA has been the subject of many court decisions, the federal regulation and guideline administrative processes, several state legislative actions, and much opining in law reviews, treatises, and social work publications. In 2011 the Washington legislature passed a comprehensive Washington State Indian Child Welfare Act (WSICWA).3 As a starting point to discussing application of the ICWA and WSICWA, it is important to review what the legislature sought to do with its comprehensive enactment.

The WSICWA is clear in setting out as its goal protection of the essential tribal relations and best interests of Indian children.4 The legislature has articulated a set of principles that must inform court decisions in ICWA/WSICWA governed proceedings:5

- Whenever out-of-home placement is necessary, the best interests of the Indian child may be served by placing the child in accordance with the WSICWA’s placement priorities.

- Where placement away from the parent or Indian custodian is necessary for the child’s safety, the placement must reflect and honor the unique values of the child’s tribal culture and must be the one that is best able to assist the child in establishing, developing, and maintaining his or her political, cultural, social, and spiritual relationship with his or her tribe and tribal community.

- The WSICWA is a step in clarifying existing laws and codifying existing policies and practices.

- The WSICWA shall not be construed to reject or eliminate current policies and practices that are not included in its provisions.

- Nothing in the WSICWA is intended to interfere with policies and procedures that are derived from agreements entered into between DSHS and a tribe or tribes, as authorized by section 1919 of the federal ICWA.

- The WSICWA specifies the minimum requirements that must be applied in a child custody proceeding and does not prevent the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) from providing a higher standard of protection to the right of any Indian child, parent, Indian custodian, or Indian child’s tribe.

- The DSHS policy manual on Indian child welfare, the tribal-state agreement, and relevant local agreements between individual federally-recognized tribes and DSHS should serve as persuasive guides in the interpretation and implementation of the federal ICWA, WSICWA, and other relevant state laws.

Congress believed the principles that underlay the ICWA’s provisions protected the best interests of Indian children.6 However, Congress also recognized that any “best interest” standard is somewhat vague and may make it difficult for judges to avoid making decisions based on their subjective values.7 The Washington legislature, mindful of this ambiguity, defined the “best interest of the Indian child” as follows:

[T]he use of practices in accordance with the federal Indian child welfare act, [the WSICWA], and other applicable law, that are designed to accomplish the following:

(a) Protect the safety, well-being, development, and stability of the Indian child;

(b) prevent the unnecessary out-of-home placement of the Indian child;

(c) acknowledge the right of Indian tribes to maintain their existence and integrity which will promote the stability and security of their children and families;

(d) recognize the value to the Indian child of establishing, developing, or maintaining a political, cultural, social, and spiritual relationship with the Indian child’s tribe and tribal community; and

(e) in a proceeding under this chapter where out-of-home placement is necessary, to prioritize placement of the Indian child in accordance with the placement preferences of [the WSICWA].8

These principles are expressed in the conjunctive not the disjunctive, and thus they are collectively the filter through which evidence must be sifted and out of which decisions must be made.

In recognition of the myriad approaches that courts have taken in implementing and applying the ICWA, and with the goal of assisting with the uniform application and implementation of ICWA, the BIA promulgated the first ever ICWA Regulations in late 2016. The final rule promotes uniform rights and protections for all Indian children subject to child custody proceedings.9 Among the provisions of the binding rule are the applicability of the ICWA, initial inquiry, emergency proceedings, notice to the tribe(s), transfer requirements and procedures, qualified expert witnesses, placement preferences, voluntary proceedings, and information, record keeping, and other rights impacted under the law. The ICWA Guidelines were updated in December 2016 and provide assistance for courts and parties involved in custody proceedings involving Indian children. While not binding, the Guidelines “explain the statute and regulations and also provide examples of best practices for the implementation of the statute, with the goal of encouraging greater uniformity in the application of ICWA.”10

§2 Child Custody Proceedings Under ICWA

The ICWA and WSICWA specifically apply to the following proceedings:

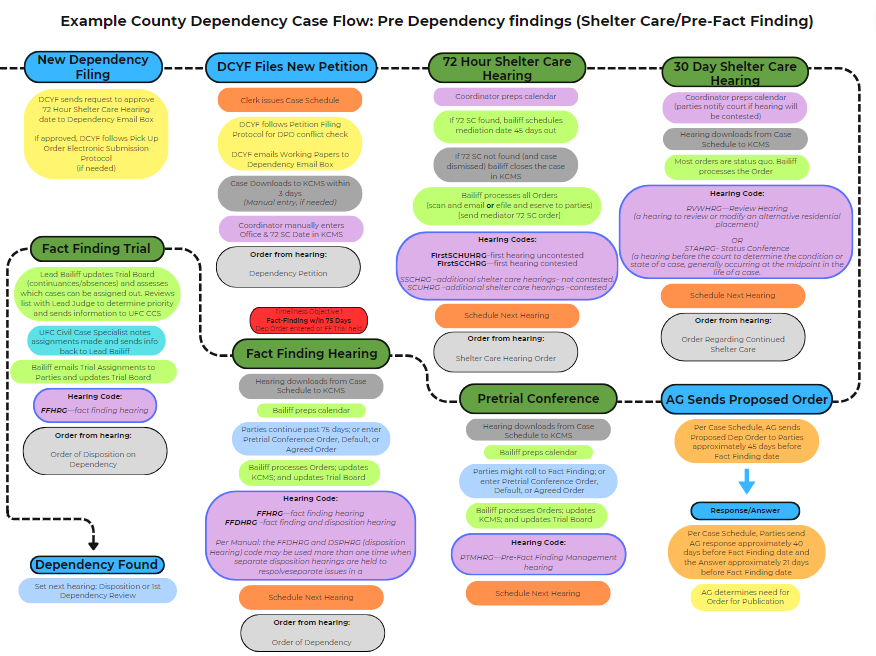

- Child in Need of Services (CHINS);11

- Shelter Care, Dependency, Termination of Parental Rights under RCW 13.34;12

- Guardianship under RCW 13.36;13

- Nonparental Custody under RCW 26.10;14

- Termination of Parental Rights and Adoption under RCW 26.33;15 and

- De facto parentage.16

By definition,17 in state court proceedings not listed above, the ICWA and WSICWA apply where an Indian child is

- Removed from the custody of a parent or Indian custodian;

- The parent or custodian cannot have the child returned upon demand, but where parental rights have not been terminated; and

- The out of home placement is NOT based on the child’s criminal activity.

- It is important to distinguish between “punishment” for a crime (in which case the ICWA and WISCWA do not apply), placement or detention because a child in a juvenile justice proceeding has no parent capable of adequately supervising the child (in which case the ICWA and WISCWA do apply), and placement based upon a “status offense” (in which case the ICWA and WISCWA do apply).18

The ICWA does NOT apply to awards of custody between biological or adoptive parents in RCW 26.09 proceedings.19

In Washington, there are no exceptions to application of the ICWA except those expressly set out in the ICWA and WSICWA.20

§3 Indian Status

There are two components to the question of “Indian status:” Who is an Indian child, and what must be done to make that determination?

An Indian child is a person under the age of 18 who is not married or emancipated, and who is either a member of an Indian tribe, or is the biological child of a member of an Indian tribe and eligible for membership in an Indian tribe.21 If a child is an Indian child, ICWA applies to his or her custody case, regardless of the Indian status of the parents.22

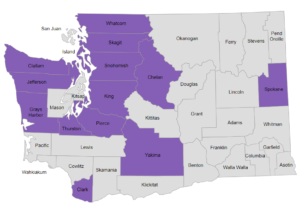

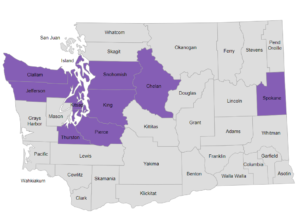

“Indian tribe” means a federally recognized tribe.23 As of October 2016, there are 566 federally recognized tribes. The complete listing of federally recognized tribes can be found at 81 Fed. Reg. 26826 (May 4, 2016).

Membership or eligibility for membership is the key, yet it is the most confusing of the elements of a child’s Indian status. Membership and enrollment are terms that are often used interchangeably. However, Congress chose the term “member” specifically intending to extend application of the ICWA to children who are not “formally enrolled” as members of an Indian tribe.24

Enrollment is not always required in order to be a member of a tribe. Some tribes do not have written rolls. Others have rolls that list only persons that were members as of a certain date. Enrollment is the common means of establishing Indian status, but it is not the only means, nor is it necessarily determinative.25

Tribal membership and tribal enrollment are not the same thing. Tribal enrollment is a process. About half of all Native Americans and Alaska Natives are formally enrolled in their Tribe. To be enrolled in a Tribe, a person must be a tribal member; membership in a Tribe is not dependent upon being enrolled. This is a very important distinction that all workers need to understand, since the ICWA applies to children who are members or eligible for membership in a Tribe, not just those who are enrolled in a Tribe.26

Washington law has long recognized that Tribes have the absolute right to determine their own membership by whatever method or however many methods or processes they determine are appropriate:

This court will not go behind the internal decision-making processes of the tribe. “A tribe’s right to define its own membership for tribal purposes has long been recognized as central to its existence as an independent political community.”

. . . .

[T]he purpose of the ICWA is, in part, to curtail state encroachment on the authority of the Indian tribes with respect to their children. . . . And “there is perhaps no greater intrusion upon tribal sovereignty than for a [nontribal] court to interfere with a sovereign tribe’s membership determination.”27

The WSICWA defines “member” and “membership” as “a determination by an Indian tribe that a person is a member or eligible for membership in that Indian tribe.”28

Washington’s recognition of a tribe’s right to definitively determine its membership was recently confirmed as appropriate approach to membership determination by the BIA in its promulgation of the 2016 ICWA Regulations (“the determination by a Tribe of whether a child is a member… is solely within the jurisdiction and authority of the Tribe… The state court may not substitute its own determination regarding a child’s membership in a Tribe.”)29 If a child is a member of or eligible for membership in more than one tribe, the decision as to which tribe the child is a member of for the purposes of ICWA application should be left to the Tribes.30

The WSICWA requires that the petitioner must make a good faith effort to determine a child’s Indian status.31 This includes, at a minimum, consultation with the child’s parents, anyone who has custody of the child, anyone with whom the child resides, and any other person who might reasonably be expected to have such information. If the petitioner has information identifying a possible tribal connection, the petitioner is expected to make contact with that tribe as well.32

In proceedings under RCW 13.34, an appointed guardian ad litem also has a duty “[t]o report to the court information on the legal status of a child’s membership in any Indian tribe or band.”33

At the first moment any party to a child custody petition appears before the court, the court must inquire about native ancestry. This will add a little extra time to the hearing, but it could save enormous amounts of time, confusion, and anguish later in the case. The court should also ask what the petitioner has done to determine that a child is or is not an “Indian child.” The court should conduct a thorough and honest inquiry and order additional investigation of the child’s native ancestry where necessary to rule out application of the ICWA. If there is a reason to believe that a child might be an Indian child, the court must confirm on the record that the agency or other party use due diligence to identify and work with all of the Tribes of which there is reason to know the child may be a member or eligible for membership and verify whether the child is a member, or a biological parent is a member and the child is eligible for membership. The court must repeat this inquiry of every participant in every subsequent child custody proceeding in the case.34 The court must treat the child as an Indian child, unless and until it is determined on the record that the child is not an “Indian child.”35

The court should also ensure that all inquiries to tribes about tribal status refer to “membership” not “enrollment.” If a tribe responds that a child is not enrolled or eligible for enrollment a further inquiry should be made as to whether the tribe has any other means or criteria for determining membership and, if so, whether those apply to the child in question.

§4 Notice

In every involuntary proceeding in a state court where the court knows or has reason to know that an Indian child is involved, the petitioning party must notify the parents, Indian custodian(s) (if applicable), and the Indian child’s tribe.36 In these cases use of a mandatory notice form is required.37 Washington’s dependency, nonparental custody, and adoption statutes require petitioners to make an affirmative allegation that the child involved is or may be an Indian child.38 Mandatory order forms in Child In Need of Services (CHINS) and At Risk Youth (ARY) proceedings require court findings that a child is or is not an Indian child.39

Upon conducting the inquiry, a court “has reason to know” an Indian child is involved under circumstances including, but not limited to:

- Any participant in the proceeding, officer of the court involved in the proceeding, Indian tribe, Indian organization, or agency informs the court that the child is and Indian child;

- Any participant in the proceeding, officer of the court involved in the proceeding, Indian tribe, Indian organization, or agency informs the court that it has discovered information indicating that the child is an Indian child;

- The child who is the subject of the proceeding gives the court reason to know he or she is an Indian child;

- The court is informed that the domicile or residence of the child, the child’s parent or child’s Indian custodian is on a reservation or in an Alaska Native village;

- The court is informed that the child is or has been a ward of a Tribal court; or

- The court is informed that wither parent or the child possesses an identification card indicating membership in an Indian Tribe.40

The 2016 Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) ICWA regulations specify service by registered or certified mail with return receipt requested.41 Registered mail may be seen as a more rigorous manner of service. WSICWA requires service by certified mail, return receipt requested.42

The BIA’s implementing regulations and Washington statutory law require that ICWA notices be sent to the person or tribal department designated by the tribe.43 It is the court’s duty to ensure that each Tribe where a child may be a member or eligible for membership receives notice. The most recent publication of tribally designated agents for receipt of ICWA notices is found at 81 Fed. Reg. 10887-10909 (March 2, 2016). If a Tribe does not designate an agent for service of ICWA notice, the petitioner should contact the Tribe to be directed to the appropriate office or individual.44

If the identity or whereabouts of the parent, Indian custodian, or the child is unknown, the notice must be served on the Secretary of the Interior, via the Regional Director.45 In Washington, service on the Secretary is made by sending the notice to the BIA Portland Regional Director.46

The original or a copy of each notice must be filed with the court along with return receipts or other proof of service.47 The petitioner bears the burden of proving that notice has been given and that the notice complies with the ICWA.48

Notice must be in clear and understandable language and include the following:

- The child’s name, birthdate, and birthplace;

- All known names of the parents, the parents’ birthdates and birthplaces, and Tribal enrollment numbers if known or available;

- If known, the names, birthdates, birthplaces, and enrollment information of direct lineal ancestors of the child;

- The name of each Indian Tribe in which the child is a member (or may be eligible for membership if a biological parent is a member);

- A copy of the petition by which the proceeding was initiated, and if a hearing has been scheduled, information on the date, time and location of the hearing;

- Statements setting out the name of the petitioner and the petitioner’s attorney; the right to intervene in the proceedings; if the parent or custodian is unable to afford counsel, they have the right to court-appointed counsel; the right to a 20-day continuance to prepare efor the custody proceeding; the right to request transfer to Tribal court; the mailing address and telephone number to the court and all parties in the matter; potential legal consequences of the custody proceeding on the future custodial rights of the parent or custodian; and the duty of confidentiality of all parties to the matter.49

The importance of the court’s and parties’ compliance ICWA’s notice provisions cannot be overstated. Early notice to all appropriate individuals and Tribal entities minimizes disruptions and promotes stability for the Indian child. Early identification of a child’s Indian status is critical to avoiding removal, placement, and other dispositional decisions that must later be reversed and which may add to the unintended impact the proceeding has on the child. Therefore, in every action that meets the ICWA/WSICWA definition of a “child custody proceeding,” the court should ensure that the petitioner has made an affirmative allegation that the child is, may be, or is not an Indian child. Where information received in court raises the prospect that the child may be an Indian child, ensure that complete and accurate notice is immediately provided to the parent, the Indian custodian, the child’s tribe (if known), any tribe with which the child may be affiliated, and the BIA.

The ICWA notice serves two purposes. First, it notifies the parent, Indian custodian, and the child’s tribe of the nature of the proceeding, where it is taking place, and important rights such as the right to counsel, the right to intervene, and the right to a continuance. This is critical to providing direction on how to participate in the proceedings. The second and equally important function is to give the BIA and the tribe or tribes who receive the notice family information that helps to identify the child as an “Indian child.” This allows the Tribes the opportunity to provide appropriate assistance and resources to the child and family. Therefore, the court should review the notice sent by the petitioner to ensure that the information is complete. Where family information is incomplete or alleged to be unavailable, the court must consider steps that may be ordered to fill in the gaps. This can be particularly challenging when the child or an ancestor of the child was adopted. Courts have appointed counsel for the child for the specific purpose of seeking information from a parent or grandparent’s sealed adoption records to determine the child’s tribal membership or eligibility for membership.50 The importance of the court’s and parties’ compliance ICWA’s notice provisions cannot be overstated. Early notice to all appropriate individuals and Tribal entities minimizes disruptions and promotes stability for the Indian child.

It is not uncommon for a tribe to respond to a proper ICWA notice indicating that it does not have enough information to make a determination about a child’s eligibility for membership. Under such circumstances the court should direct the petitioner to contact the tribe (either the agent designated in the federal register or the tribe’s Indian Child Welfare (ICW) program) to find out what specific information is needed. The petitioner’s efforts in this regard should be documented in the court record.

The 2016 ICWA regulations require the state court to inquire of “each participant in an emergency, or voluntary or involuntary child-custody proceeding” to state on the record whether there is a reason to believe the child is an Indian child.51 As the language indicates, this inquiry should be made at every hearing in a case, even if it has previously been determined that the child is not an Indian child. This provision recognizes that a child’s Indian status may have changed, or that additional information may have come to light that would alter this finding. The court must instruct the parties to inform the court if they receive subsequent information that a child might be an Indian child.52

Washington law contains the notice requirement to those proceedings that would be characterized as voluntary, such as voluntary relinquishment of parental rights, preadoptive placement, and adoption.53

Except where the court is exercising emergency jurisdiction pursuant to 25 U.S.C. § 1922, it is important that no hearing take place sooner than 10 days from the date of receipt of the notice by the parent, Indian custodian(s), and tribe.

Perhaps most important to any discussion or consideration of the ICWA’s notice requirements is that failure to provide proper notice is grounds for invalidating the court’s action.54 This statutory provision has resulted in the disruption of long standing adoptions and the return of children to their parents after many years. Without arguing the benefit or harm that can result from such an outcome, it is painfully clear that decisions that are made in full compliance with the ICWA provide the greatest assurance of finality. Exercising an abundance of caution and providing notice where there is only scant indication of possible tribal affiliation may involve extra effort and expense. Avoiding the consequences described in this paragraph is well worth that added effort and expense. For more information on invalidating court orders, see § 29.11 Petition to Invalidate State Court Orders.

Once proper notice has been served, a written determination or testimony by a tribe that the child is a member or is eligible for membership is conclusive.55 If a tribe makes a determination that a child is not a member or eligible for membership, that is conclusive as to that tribe.56 However, either finding by the court is justified only where the tribe’s response come from, someone within the tribe that has authority to make the determination.57 If no authorized tribal representative responds to a notice, the court cannot construe the nonresponse as the tribe’s decision that the child is not a member or eligible for membership.58 However, under such circumstances the party asserting application of the ICWA/WSICWA will have the burden of establishing the child’s Indian status.

Finally, during the pendency of a child custody proceeding, it is possible a child’s Indian status will change. Tribes may change the basis upon which they determine their membership, a tribe may gain federal recognition,59 or new evidence may help a tribe make a more accurate determination.60 This reality underscores the importance of the court’s ongoing inquiries regarding the child’s Indian status throughout the pendency of a child custody action.

§5 Jurisdiction

§5a Exclusive Jurisdiction

The tribal court has exclusive jurisdiction over child custody proceedings involving Indian children who reside or are domiciled on the reservation of a federally recognized Indian tribe whether or not that tribe is the child’s tribe.61 Once a child has been made a ward of a tribal court that tribal court has and retains exclusive jurisdiction regardless of the child’s residence or domicile.62 If a state court determines that either of these jurisdictional conditions exists in a case before it, the court must expeditiously notify the tribal court of the pending dismissal based on the Tribe’s exclusive jurisdiction, dismiss the state court action, and send all information regarding the proceeding to the tribal court.63

§5b Exception to Exclusive Jurisdiction

Under the ICWA, there is an exception to a tribe’s exclusive jurisdiction where existing federal law otherwise vests jurisdiction in the state.64 Until passage of the WSICWA, the “existing Federal law” proviso in § 1911(a) included a federal law popularly referred to as “Public Law 280,” which gives certain states . . . limited jurisdiction over civil causes of action that arise in Indian country.”65

The WSICWA, however, recognizes the exclusive jurisdiction of all tribes irrespective of P.L. 280. The only exceptions now are where a tribe “has consented to the state’s concurrent jurisdiction, expressly declined to exercise its jurisdiction, or where the state is exercising emergency jurisdiction in strict compliance with section 14 of [the WSICWA].”66

§5c Concurrent Jurisdiction

The ICWA establishes concurrent but presumptively tribal jurisdiction in the case of an Indian child not domiciled or residing on a federally recognized tribe’s reservation.67 Thus, a child custody proceeding involving an Indian child not domiciled or residing on an Indian reservation, may begin in either state court or the child’s tribe’s court.

§5d Transfer of Jurisdiction

Under ICWA, where the state and tribal court have concurrent jurisdiction and an ICWA proceeding begins in state court, the child’s parent(s), Indian custodian(s), or the child’s tribe can petition to transfer the proceeding to the child’s tribe’s court.68 WSICWA extends the right to petition to transfer proceedings to the child, if age 12 or older.69

Either parent has absolute veto power over the transfer.70 If neither parent objects to the transfer, and the tribal court accepts transfer, the court must transfer the proceeding to tribal court, absent good cause.71

In foster care or termination of parental rights proceedings, a request to transfer may be made at any stage of the proceedings orally on the record or in writing.72

Parents do not lose their veto power through their own misconduct such as failing to comply with court-ordered services.73 Although an Indian custodian or child over age 12 can request a transfer, he or she cannot veto a transfer.74

§5e Declination of Transfer

Just as a parent can veto transfer of a child custody proceeding to tribal court, a tribe can decline to accept jurisdiction when a request for transfer has been made.75 A tribal court’s decision to decline jurisdiction does not have any impact on the tribe’s right to intervene and participate in the state court child custody proceeding pursuant to 25 U.S.C. § 1911(c).

This section applies only where there is a request for transfer of jurisdiction to a tribal court where the state court has proper concurrent jurisdiction.

Transfer to tribal court must occur upon a proper request unless there is a parental veto, the tribal court declines transfer, or good cause is shown to deny transfer.76 “The burden of establishing good cause by clear and convincing evidence is on the party opposing the transfer.”77

When transfer takes place, the tribe takes full authority of the case and the state court is no longer involved. Absent an agreement between DSHS and the tribe, DSHS’s role in case management will end as well, with the tribe’s child welfare agency assuming case management duties. This does not automatically mean that a child’s placement in a parent’s or Indian custodian’s home, relative care, foster care, or a preadoptive placement will be changed. Nor does it automatically mean that the child will be moved to or placed in the tribal community.

A request for transfer can be made at any time during a foster care or termination of parental rights proceeding.78

Good cause to deny transfer exists when the Indian child’s tribe does not have a “tribal court” as defined by the ICWA.79 Good cause to deny transfer may be found where the evidence necessary to decide the case could not be adequately presented in the tribal court without undue hardship to the parties or the witnesses.80 This may appear to increase the likelihood that transfer will be denied the further the tribe’s reservation is from the state court. However, distant tribes may be able to conduct proceedings in the family’s community; utilize court facilities of tribes that are much closer to the family, witnesses, and evidence; or take advantage of videoconferencing technologies that allow the tribal court to conduct a hearing without the parties or witnesses leaving their own community.81

The 2016 ICWA Federal Regulations specifically prohibit courts from considering the following circumstances as “good cause”:

- Whether the proceeding is at an advanced stage, if the Indian child’s parent, Indian custodian, or Tribe did not receive notice of the child custody proceeding until an advanced stage;

- Whether there have been prior proceedings involving the child for which no petition to transfer was filed;

- Whether transfer could affect the placement of the child;

- The Indian child’s cultural connections with the Tribe or its reservation; or

- Socioeconomic conditions or any negative perception of Tribal or Bureau of Indian Affairs social services or judicial systems.82

There are two circumstances where good cause to deny transfer due to the advanced stage of the proceeding must be done with extreme caution. First, take caution when the parent(s), Indian custodian(s), or tribe has not received timely notice of the proceeding (as when, through no fault of the tribe, the child’s Indian status is determined late in the proceeding). It may be appropriate for the court to make a robust factual inquiry into parties’ efforts to determine whether the child was an Indian child throughout the proceedings. Aside from promoting greater diligence by petitioners, placement and service decisions made without application of the ICWA or without the input of the child’s tribe may lack consideration—careful or otherwise—of the principles of the ICWA or application of its procedural and evidentiary requirements. Denial of transfer under such circumstances would likely compound the problems created by these failures.

Second, and more challenging for state courts, is the reluctance of many tribes to seek transfer at the outset of a state court child custody proceeding, particularly one initiated in a state a great distance from the tribe’s reservation. This is often the result of the tribe’s recognition that, assuming the state court properly applies other provisions of the ICWA, a family in a distant community may have a greater chance for successful reunification if the services and supports to address the family’s problems are ordered by a court in the community where the family intends to continue living and which has greater familiarity with the service providers. However, that same tribe may seek transfer once permanency planning begins or when it appears that the services may be failing. This is particularly true where the petitioner is proposing termination and adoption permanency—options that may be anathema to the tribe’s core values and practices concerning child rearing and family structure.

It should also be noted that termination of parental rights is accomplished by a separate proceeding. When termination petitions are filed and served on the child’s tribe and the tribe or parent(s) immediately respond with a motion to transfer, then “good cause due to the advanced stage of the proceeding” is not applicable.

The WSICWA establishes a set of basic procedures for transfer of jurisdiction.83 Where a motion to transfer is received from a party other than the child’s tribe and the child’s tribe has not intervened, the moving party must give notice to the child’s tribe including a copy of the motion and any supporting pleadings. When the court orders transfer, that ruling is communicated to the tribal court to which jurisdiction is being transferred. While the state court awaits receipt of an order from the tribal court accepting jurisdiction, it can continue to hold hearings and take actions necessary to child’s interests so long as those are done in strict compliance with the ICWA/WSICWA. The state court cannot enter a final order except an order dismissing the action and returning the child to the care of the parent or Indian custodian from which the child had been removed. The tribal court has 75 days within which it must respond. It may decline to accept jurisdiction or it may enter an order accepting jurisdiction. Upon receipt of an order accepting transfer, the state court enters an order dismissing the proceeding. If the state court does not receive a response within 75 days it can assume transfer has been declined, enter an order vacating the order to transfer, and proceed with the dependency.84

§5f Emergency Jurisdiction

Irrespective of the jurisdictional, notice, and other procedural requirements of the ICWA and WSICWA, a state court can exercise jurisdiction to affect emergency removal of an Indian child in order to prevent imminent physical damage or harm to the child.85 The specific language of this provision appears to limit its application to children who are residents of or domiciled on a reservation, but temporarily located off the reservation.86

If this reading were correct, however, the statute would not then go on to allow the social services agency to initiate a child custody proceeding or to transfer the child to the jurisdiction of the appropriate Indian tribe . . . . Moreover, it would make no sense to give a state more power to make an emergency placement of an Indian child who lives on a reservation than one who lives off the reservation. Thus, as the legislative history confirms, Congress intended this section to apply to emergency removals and placements of all Indian children.87

Exercise of this emergency jurisdiction essentially allows for temporary suspension of some, most, or all of the procedural and notice requirements of the ICWA and WSICWA. The ICWA and WSICWA require that when the court makes a finding on the record that emergency removal is necessary to prevent imminent physical damage or harm88, the emergency removal or placement terminates immediately when such removal or placement is no longer necessary to prevent such damage or harm to the child.89 The petition alleging the need for emergent removal or continued emergency placement should contain a statement of the risk of imminent physical damage or harm and any evidence that removal is necessary, as well as the child’s name, age, and last known address; the name and address of the parents / custodians; the steps taken to provide notice to the parents, custodians, and Tribe about the emergency proceedings; if the child’s parents and custodians are unknown, an explanation of efforts to find and contact them; the residence and domicile of the Indian child, including whether the residence or domicile is on a reservation; the Tribal affiliation if the child and the parents or custodians; if exclusive jurisdiction resides with the Tribe, the efforts made to contact the Tribe and transfer jurisdiction; and a statement of the efforts that have been made to assist the parents/custodians so the child can safely be returned to their custody.90

Given the extraordinary deviation from ICWA protections this circumstance authorizes, 25 C.F.R. 23.113(e) states that the emergency proceeding should not be continued for more than 30 days unless the court determines that restoring the child to the parent or custodian would subject the child to imminent physical damage or harm; the court has not been able to transfer the proceeding to the jurisdiction of the appropriate Tribe; and it has not been possible to initiate a “child custody proceeding” as defined in 25 C.F.R. 23.2.91 “Imminent physical damage or harm” means “immediately threatened with harm, including when there is an immediate threat to the safety of the child, when a young child is left without care or adequate supervision, or where there is evidence of serious ongoing abuse and the officials have reason to fear immediate recurrence.”92

Courts must carefully scrutinize the facts to determine whether the “emergency situation” continues to exist after the child’s removal. ICWA and the rule make it clear that an “emergency” must be a short as possible.93 If the court does not find that the emergency continues, it must return the child to the parent, transfer the proceeding to the tribal jurisdiction, or the petitioner may initiate a child custody proceeding, which would provide all the protections of ICWA.

§5g Full Faith and Credit

The federal government, state agencies, and state courts must give full faith and credit to the “public acts, records, and judicial proceedings” of a federally recognized tribe relating to child custody proceedings.94 This includes tribal court decisions, orders, or decrees concerning any of the types of proceedings covered under 25 U.S.C. § 1903(1). The names of the causes of action may be different from their counterparts in state court, and the adjudicatory body may not be a “court” as that term would be understood in the state judicial system. However, it need only be the process and body that is authorized under the tribe’s law to address the range of child custody matters described in the ICWA. Unlike a tribe’s decision about tribal membership, in its decision to give full faith and credit to a tribal court order the state court may look behind the entry of tribal court orders to determine whether the tribal court had proper personal and subject matter jurisdiction under the tribe’s laws and whether the parties were afforded due process.95

§6 Intervention

In any state court proceeding for the foster care placement of or termination of parental rights to an Indian child, the Indian custodian(s) of the child and the Indian child’s tribe shall have a right to intervene at any point in the proceeding.96 The “Indian custodian” is a person who is a member of a federally recognized tribe and who has legal custody of the child under state or tribal law or custom, or to whom temporary physical care, custody, and control has been transferred by the child’s parent.97 The “child’s tribe” is a federally recognized Indian tribe in which the child is a member or is eligible for membership.98 Under the ICWA if a child is a member or eligible for membership in more than one tribe, the “child’s tribe” is the tribe with which the child has the more significant contacts.99 The WSICWA does not contain such a limitation, instead recognizing any tribe in which a child is a member or eligible for membership as the child’s tribe.100

The right to intervene is clear, unambiguous, and absolute. The state court has no authority to prevent the Indian custodian(s) or the child’s tribe from intervening, and these parties need not seek the permission of the court to intervene. There is no accepted or required form or procedure for intervention pursuant to the ICWA or WSICWA. Rather, the court may receive a motion to intervene or it may simply receive a notice of intervention. Any of the parties may object, and the court may require an evidentiary hearing to determine whether an intervenor meets the ICWA/WSICWA definitions of “Indian custodian” or “Indian child’s tribe.” However, there is no other basis for granting a party’s objection. The court may also consider a request for permissive intervention under CR 24(b) for individuals and tribes who have a vital interest in the child, but who do not meet the ICWA/WSICWA definitions.101

The Congressional findings and declaration of policy and the Washington legislature’s intent language articulate the importance of the child’s tribe. The process of identifying and supporting relative placements, services, and permanency planning is greatly enhanced by having more tribal involvement. Where such circumstances exist and there are conflicting views or opinions between the tribes, the DSHS has trained and experienced ICW workers up to and including the ICW program Manager in Olympia who can facilitate the conversation necessary for reaching consensus.

It should also be noted that the decision of the child’s tribe not to intervene does not change the requirement for proper application of all other procedural and evidentiary requirements of the ICWA.

§7 Appointment of Counsel

An important protection for parents and Indian custodians under the ICWA and WSICWA is the right to court-appointed counsel in any removal, placement, or termination proceeding where the court determines indigence.102 The state courts are familiar with the procedures for payment of court-appointed counsel in dependency and termination proceedings. However, court-appointed counsel for indigent parents and Indian custodians is required in every type of proceeding covered by the WSICWA.103 Federal regulations describe the process for application for payment of attorney fees through the Department of the Interior.104

These same provisions also authorize appointment of counsel for the child when the court determines that it is in the child’s best interest. Court appointed counsel for the child is now mandated for children who have been “legally free” for six months.105

§8 Requirements for Involuntary Proceedings

§8a Active Efforts

A party seeking involuntary removal of an Indian child from his or her parent or Indian custodian, or the involuntary termination of parental rights, must satisfy the court that “active efforts have been made to provide remedial services and rehabilitative programs designed to prevent the breakup of the Indian family and these efforts have proved unsuccessful.”106 Contained in the “active efforts” language are two general requirements: first, the degree to which the social worker engages the parent in the service plan; and second, the character of services offered and actually provided by that plan.

The ICWA drafters considered the character of social work practice then common around the country and chose “active efforts” as a term that articulated a requirement for a significantly increased level of engagement with parents/Indian custodians than that required by the “reasonable efforts” standard so often employed in child welfare cases. In addition, the drafters demanded significant effort on the part of social workers to facilitate receipt of targeted services by the parents/Indian custodians:

Passive efforts are where a plan is drawn up and the client must develop his or her own resources towards bringing it to fruition. Active efforts, the intent of the drafters of the Act, is where the state caseworker takes the client through the steps of the plan rather than requiring that the plan be performed on its own. For instance, rather than requiring a client to find a job, acquiring new housing, and terminate a relationship with what is perceived to be a boyfriend who is a bad influence, the Indian Child Welfare Act would require that the case worker help the client develop job and parenting skills necessary to retain custody of her child.107

“Active efforts” has been defined as “affirmative, active, thorough, and timely efforts intended primarily to maintain or reunite an Indian child with his or her family”.108 The petitioner must document the active efforts in detail in the court record before requesting foster care of termination of parental rights.109 Prior to ordering involuntary foster care placement or a termination of parental rights, a court must conclude that active efforts have been made to prevent the breakup of the Indian family, and that those efforts have been unsuccessful.110 The Regulations include eleven examples of active efforts, emphasizing the engagement of families in accessing services.111 These examples represent best practices, but are not intended to be an exhaustive list, as a caseworker’s “active efforts” should be tailored to the individual needs of each family.112

The BIA Regulations address the second component of the “active efforts” provision—the design of services and programs aimed at Indian families. “To the maximum extent possible, active efforts should be provided in a manner consistent with the prevailing social and cultural conditions and way of life of the Indian child’s Tribe and should be conducted in partnership with the Indian child and the Indian child‘s parents, extended family members, Indian custodians, and Tribe.”113 The services must be relevant and appropriate to the needs of the child and parents. In all such proceedings prior to the placement of a child in foster care, efforts must be made to prevent or eliminate the need for removing the child from the child’s home and, when a child has to be removed, to make it possible for a child to safely return to the child’s home.114 This means services specifically targeted at the parent’s parenting deficiencies.

Under the WSICWA where DSHS is the petitioner, the active efforts provision requires DSHS to make timely and diligent efforts to work with and engage the parents or Indian custodian in culturally appropriate preventative, remedial, or rehabilitative services; whenever possible those must be services offered by tribes and Indian organizations.115 Where the petitioner does not have a statutory or contractual obligation to directly provide or procure services (i.e., nonparental custody), the petitioner must document a concerted and good faith effort to the parents’ or Indian custodian’s receipt of and engagement in culturally appropriate preventative, remedial, or rehabilitative services and includes services offered by tribes and Indian organizations, whenever possible.116

The active efforts requirement persists throughout the duration of a dependency.117 While there are no specific time requirements for active efforts provision, throughout the case the court must inquire whether the agency has made active efforts to provide services during that reporting period, taking into account whether circumstances have changed, requiring additional active efforts.118

The Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) relieves states of the “reasonable efforts” requirement where a parent’s behavior has been more egregious:

“[R]easonable efforts…shall not be required to be made with respect to a parent of a child if a court of competent jurisdiction has determined that:

(i) the parent has subjected the child to aggravated circumstances (as defined in State law, which definition may include but need not be limited to abandonment, torture, chronic abuse, and sexual abuse);

(ii) the parent has(I) committed murder…of another child of the parent;

(iii) committed voluntary manslaughter…of another child of the parent;

(iv) aided or abetted, attempted, conspired, or solicited to commit such a murder or such a voluntary manslaughter; or

(v) committed a felony assault that results in serious bodily injury to the child or another child of the parent; or

(vi) the parental rights of the parent to a sibling have been terminated involuntarily.119

However, ASFA does not modify the ICWA. Irrespective of the parental behavior that necessitates the dependency or termination proceeding, in a child custody proceeding involving an Indian child, the state is required to make active efforts.120

The court should make sure that services address the parenting deficiencies that necessitated the child custody proceeding. It is important to determine that the “problem” represents a danger to the child, such as drug or alcohol addiction creating dangerous conditions in the home, and not a cultural bias such as a child appearing to reside as much of the time in the home of extended family members as in the home of the parent.

The court should make sure the services that are offered are culturally relevant to the parent or Indian custodian. For instance, active efforts to address drug or alcohol issues cannot be shown if there is no consideration of the cultural relevance of the treatment modality of an offered treatment program.

The court should make sure that the petitioner has made significant effort to engage the parent or Indian custodian in the services. A caseworker may put tremendous effort into identifying services and making referrals only to have all that effort wasted because there is something fundamentally culturally inappropriate in the manner in which the caseworker communicates or tries to work with the parent or Indian custodian that virtually guarantees failure.

Where a parent has failed to complete the service or has not benefited from the service, the court should inquire as to the cultural competence of the service provider. Finally, where a parent or Indian custodian fails to engage in services (or to participate in the child custody proceeding) the court must consider the cultural implications of that behavior. The ICWA, including the requirement for active efforts, is intended to overcome the legacy of mass permanent removal of Indian children from their families, tribes, culture, and community. The trauma this has caused to Indian people continues to affect parents today, both in their parenting and their response to intervention by child protection agencies.121

A challenging aspect of the ICWA active efforts provisions is that they do not designate a standard of evidence for assessing whether active efforts have been provided. However, the Guidelines for Implementing the Indian Child Welfare Act state that the Department of the Interior “favorably views cases that apply the same standard of proof for the underlying action to the question of whether active efforts were provided (i.e. clear and convincing evidence for foster care placement and beyond a reasonable doubt for TPR).”122 The “qualified expert witness” discussed below in § 29.8d can be a valuable resource to the court in assessing whether the active efforts requirement has been met.

Finally, the Washington legislature was mindful of the significant collaborative efforts made by DSHS and Washington tribes to develop policies and practices that best serve and protect Indian children and families. These policies and practices are contained in the Children’s Administration’s Indian Child Welfare Policy Manual,123 the Tribal-State Agreements regarding jurisdiction124, and local agreements that have been entered into, or are in the process of development between individual tribes and DSHS.125 The Washington legislature specifically identified these documents as the “persuasive guides” for implementation and interpretation of the ICWA and WSICWA.126 When the court determines whether “active efforts” have been made, reference to the expectations set out in these agreements is vital.

§8b Evidentiary Standards

The court must not order a foster care placement of an Indian child unless clear and convincing evidence is presented, supported by the testimony of one or more qualified expert witnesses, demonstrating that the child’s continued custody with parent or Indian custodian is likely to result in serious emotional or physical damage to the child.127 The standard of proof increases to “beyond a reasonable doubt” when the proceeding is for the termination of parental rights.128 There must be a causal relationship between the conditions in the home and likelihood that the child will be subject to serious emotional or physical damage.129 The BIA Regulations instruct that without that causal relationship established,

“[e]vidence that only shows the existence of community or family poverty, isolation, single parenthood, custodian age, crowded or inadequate housing, substance abuse, or nonconforming social behavior does not by itself constitute clear and convincing evidence or evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that continued custody is likely to result in serious emotional or physical damage to the child.130

This interpretation focuses on the parent’s or Indian custodian’s current unfitness, and its related impact on the child’s wellbeing.

In the only Washington case to sort through the requirements of this provision, the court held that even where there is no showing of present parental unfitness, the court may take into consideration emotional and psychological damage from prior unfitness of a parent and the child’s current special needs for treatment and care.131 Despite the court’s look backwards at the behavior or deficits of the parent, the facts before the court demonstrated that the children faced inevitable and overwhelming peril if immediately returned to the care of their parent.

As expressed in the BIA’s guidelines, blanket determinations of risk based on certain conditions are disfavored under Washington law. For instance, “exposure to domestic violence as defined in RCW 26.50.010 that is perpetrated against someone other than the child does not constitute negligent treatment or maltreatment in and of itself.”132

Where parental deficits have persisted for a sufficient period of time to indicate that continuing efforts are unlikely to reduce the likely risk of harm to the child, permanent placement away from the parent or the Indian custodian is considered in the child’s best interest. This determination is based on the parent(s) or Indian custodian(s) having failed to reduce the risk he or she poses to the child. However, this harm should be distinguished from the anticipated harm that disrupting the psychological bond of an Indian child to a foster or prospective adoptive parent might cause. Bonding and attachment to the foster or preadoptive parent is not to be used as the sole basis or primary reason for finding that return to the parent is likely to result in serious emotional or physical damage to the child.133 Additionally, a placement may not depart from the placement preferences outlined in ICWA based solely on ordinary bonding that flowed from time spent in a non-preferred placement that was made in violation of the law.134

§8c Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl135

This case asked the United States Supreme Court to determine whether and how to apply the ICWA where an Indian child’s unwed, non-Indian mother sought voluntary termination of her parental rights and adoption of her child by a non-Indian, non-relative couple over the objection of the unwed Indian father. The Court limited its ruling to the evidentiary requirements for termination of parental rights. Concerning the 1912(d) requirement for “active efforts,” the Court reasoned that the sole purpose of that requirement was to “prevent the breakup of the Indian family.” Because the father never had legal or physical custody of the child, there was no Indian family to break up. Thus, active efforts were not a prerequisite to termination of the father’s rights.136 This analysis was subsequently dubbed the “Existing Indian Family” doctrine. Similarly, the Court reasoned that ICWA required a heightened standard of evidence showing “continued custody” would likely endanger the child. Again, where the father never had legal or physical custody of the child, 1912(f) was not applicable.137

The Court relied, in part, on the fact that the law in Oklahoma (the state of the child’s birth) and in South Carolina (the state in which the adoption proceeding was initiated) law, vests all parental rights in the unwed mother unless the state court orders otherwise. However, when paternity is acknowledged or established, Washington law confers upon the father all of the rights and duties of a parent.138 In other words, a man whose paternity of an Indian child has been acknowledged or established under Washington law would be deemed to have “legal” custody equal to that of the mother unless and until a court orders otherwise. Thus, that part of the legal rationale underlying Adoptive Couple would have been inapplicable in Washington.

More importantly, the WSICWA expressly extends the protection of these evidentiary standards (and the rest of its provisions) to acknowledged and established fathers.139 Further, an alleged father must be notified that if he acknowledges or establishes paternity these evidentiary standards will be applied to him as well.140 Washington law clearly provides that a non-consenting alleged father who merely claims paternity cannot have his parental rights involuntarily terminated unless the ICWA’s evidentiary standard is met.141

Application of the “active efforts” requirement and the standard of evidence in termination cases under the WSICWA to all parents who meet the definition of “parent,” irrespective of marital status or the noninvolvement of the parent in the care, support, or supervision of the child could not be clearer. The ICWA’s mandate to apply state law where it provides a higher level of protection to the rights of the parent render’s Adoptive Couple meaningless and inapplicable in Washington.142

Perhaps in direct response to Adoptive Couple, the 2016 Regulations legally bind all courts to a definition of “custody” and “continued custody” that includes any legal and/or physical custody of a child by a parent or Indian Custodian under any applicable tribal, customary, or state law.143 The rule further states that this “continued custody” exists whenever a parent or Indian custodian has had custody “at any point in the past.”144

§8d Qualified Expert Witnesses

The “clear and convincing” standard in involuntary foster care proceedings and the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard in termination proceedings both require that the evidence include the testimony of qualified expert witnesses.145

The “qualified expert witnesses” requirement has been hotly debated in trial courts and has had numerous definitions and permutations applied to it over the years. The 2016 Federal Regulations state that any “qualified expert witness” should be able to testify as to the prevailing social and cultural standards of the Indian child’s Tribe. Tribes may designate individuals as qualified to testify as to the prevailing social and cultural standards of the Indian child’s Tribe. Any party or the Court may request assistance from the Tribe or the BIA in locating persons qualified to serve as expert witnesses.146

The WSICWA clarifies that a “qualified expert witness” is “a person who provides testimony in a proceeding under [the WSICWA] to assist a court in the determination of whether the continued custody of the child by, or return of the child to, the parent, parents, or Indian custodian, is likely to result in serious emotional or physical damage to the child.”147 The petitioner must ask the child’s tribe to identify such an expert at least twenty days prior to any evidentiary hearing in which the testimony of the witness is required. Where the child’s tribe is not involved in the case or does not respond to the request to identify a qualified expert witness, in descending order of preference, the petitioner must provide148

(i) A member of the child’s Indian tribe or other person of the tribe’s choice who is recognized by the tribe as knowledgeable regarding tribal customs as they pertain to family organization or child rearing practices for this purpose;

(ii) Any person having substantial experience in the delivery of child and family services to Indians, and extensive knowledge of prevailing social and cultural standards and child rearing practices within the Indian child’s tribe;

(iii) Any person having substantial experience in the delivery of child and family services to Indians, and knowledge of prevailing social and cultural standards and child rearing practices in Indian tribes with cultural similarities to the Indian child’s tribe; or

(iv) A professional person having substantial education and experience in the area of his or her specialty.

Where the state agency is the petitioner, the qualified expert witness cannot be the currently assigned caseworker149 or the caseworker’s supervisor.150. Congress noted in passing ICWA in 1978 that “[t]he phrase ‘qualified expert witness’ is meant to apply to expertise beyond normal social worker qualifications.”151

ICWA and the 2016 Federal Regulations do not limit the number of expert witnesses that may testify. The court may accept expert testimony from any number of witnesses, including from multiple qualified expert witnesses.152

§9 Placement of an Indian Child

The Congress hereby declares that it is the policy of this Nation to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by the establishment of minimum Federal standards [and] . . . the placement of such children in foster or adoptive homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian culture. . . .153

This Congressional policy is repeated in the “intent” section of the WSICWA and further expresses the intention to assure placements that can assist the Indian child to establish, develop, and maintain his or her political, cultural, social, and spiritual relationship with his or her tribe and tribal community.154

When a state court undertakes any child custody proceedings, it must require participants to state on the record whether the child is an Indian child, or whether there is reason to believe the child is Indian. Unless or until the child is determined not to be Indian, the Court must ensure that the child’s placement conforms with the ICWA’s placement preferences.155

In the absence of good cause to the contrary, preference in adoptive placements is given first to a member of the child’s extended family, second to other members of the Indian child’s tribe, and third to other Indian families.156 Again, the WSICWA mirrors this list of preferences.157 However, the WSICWA gives preference at the third level to Indian families of a similar culture to the child’s tribe prior to other Indian families.158

The provisions relating to foster care and preadoptive placement are the same in the ICWA and WSICWA, requiring placement within reasonable proximity to the child’s home in the least restrictive setting which most approximates a family and which meets any special needs the child may have.159

Similarly, in the absence of good cause to the contrary, preference in foster care or preadoptive placement is given first to a member of the Indian child’s extended family; second to a foster home licensed, approved, or specified by the Indian child’s tribe; third to an Indian foster home licensed or approved by an authorized non-Indian licensing authority; and fourth to an institution for children or child foster care agency approved by an Indian tribe or operated by an Indian organization which has a program suitable to meet the Indian child’s needs.160

The child’s tribe can establish a different order of preference for adoptive, preadoptive, or foster care placements through a tribal resolution.161 The court must follow the alternative preferences so long as the placement is the least restrictive setting appropriate to the particular needs of the child.162 The court is required to consider a parent’s request for anonymity in voluntary proceedings when applying tribal preferences.163 The standards to be applied in meeting the preference requirements of this section shall be the prevailing social and cultural standards of the Indian community in which the parent or extended family resides or with which the parent or extended family members maintain social and cultural ties.

What constitutes “good cause” to deviate from the statutorily mandated placement preferences has been the source of significant litigation since the passage of the ICWA. The 2016 Federal Regulations provide both procedural and substantive clarity to the inquiry required of the court in assessing this question. Any party asserting that good cause exists must state the reasons for that belief either orally on the record or in writing to all parties and the court.164 The party seeking the departure has the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that good cause exists.165 The court’s determination that good cause exists must be made either on the record or in writing, and should be based on the following considerations:166

- The request of one or both of the Indian child’s parents, if they attest that they have reviewed the placement options, if any, that comply with the order of preference;

- The request of the child, if the child is of sufficient age and capacity to understand the decision that is being made;

- The presence of a sibling attachment that can be maintained only through a particular placement;

- The extraordinary physical, mental, or emotional needs of the Indian child, such as specialized treatment services that may be unavailable in the community where families who meet the placement preferences live;

- The unavailability of a suitable placement after a determination by the court that a diligent search was conducted to find suitable placements meeting the preference criteria, but none had been located. For purposes of this analysis, the standards for determining whether a placement is unavailable must conform to the prevailing social and cultural standards of the Indian community in which the Indian child’s parent or extended family resides or with which the Indian child’s parent or extended family maintain cultural ties.167

The Federal Regulations additionally clearly specify that a court may not depart from preference priorities based on the socioeconomic status of any placement relative to another placement. Ordinary bonding or attachment that results from time spent in a non-preferred placement made in violation of the ICWA cannot be the sole basis from a continued departure from the placement preferences.168

In Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, the United States Supreme Court held “Section 1915(a)’s adoption-placement preferences are inapplicable in cases where no alternative party has formally sought to adopt the child.”169 However, as noted above, WSICWA and Washington’s adoption statute make no room for exception for their application. Washington’s adoption statute is very clear that only if the court determines that the adoptive parents are within the placement preferences of RCW 13.38.180, or good cause to the contrary has been shown on the record, may the court enter a decree of adoption pursuant to RCW 26.33.250.170

§10 Consent

Child custody proceedings under the ICWA may be either voluntary or involuntary. Involuntary proceedings are those in which a child is removed over the objection of the parent or Indian custodian and is placed in the custody of someone other than the parent or Indian custodian, parental rights are terminated over the objection of the parent, or the child is adopted over the objection of the parent. Voluntary proceedings involve agreed foster care placement, relinquishment of parental rights, or consent to adoptive placement.

Consent to foster care placement, relinquishment of parental rights, or an adoptive placement is not valid unless

(1) It is in writing;

(2) It is recorded before a judge in a court of competent jurisdiction; and

(3) The judge certifies that the terms and consequences of the consent were

a. Fully explained by the court in the parent or Indian custodian’s primary language (or translated);

b. Fully understood by the parent or Indian custodian; and

c. Given at more than 10 days after the birth of the child.171

The consent document signed by the parent or Indian custodian and filed with the court must contain specific information to be valid. If there are any conditions to the consent, these must be clearly set out. A written consent to foster care should contain the name and birthdate of the Indian child; the name of the child’s Tribe; the Tribal enrollment number for the parent and the child, where known, or some other indication of the child’s membership in the Tribe; the name, address, and other identifying information about the consenting parent or Indian custodian; the name of the person or entity that arranged the placement; and the name and address of the prospective foster parent, if known.172 If confidentiality of the parent’s identity is requested or indicated, execution of consent may not need to be in open court, but still must be made before a court of competent jurisdiction in compliance with the ICWA, the federal rules, and state law.173

Consent to voluntary foster care placement can be withdrawn for any reason at any time during the placement.174 To withdraw consent, the parent or Indian custodian must file a written document with the court or testify before the court. If a parent or Indian custodian withdraws consent, the court must ensure that the child is returned to that parent or custodian as soon as practicable.175

Consent to relinquishment of parental rights can be withdrawn for any reason at any time prior to entry of a final decree of termination and have the child returned.176 Consent to an adoptive placement may be withdrawn for any reason prior to the entry of the final decree of adoption, and have the child returned home.177 To withdraw consent, the parent or Indian custodian must file a written document with the court or testify before the court. The court in which the withdrawal of the consent is filed must promptly notify the person or entity who arranged the placement of such filing and the Indian child must be returned to the parent or Indian custodian as soon as practicable.178

The ICWA does not give a parent the right to revoke his or her consent to an adoption after a final order terminating that parent’s rights has been entered.179 The WSICWA, however, does offer a mechanism for the withdrawal of consent if that consent was obtained through fraud or duress, thus vacating the decree.180 See Sec. 29.11 for more information on the requirements for this action.

upon the grounds that consent was obtained through fraud or duress. Upon a finding that such consent was obtained through fraud or duress the court shall vacate the decree and return the child to the parent. No adoption which has been effective for at least two years may be invalidated under this section unless otherwise allowed by state law.

§11 Petition to Invalidate State Court Orders

If a state court has removed an Indian child from a parent or Indian custodian or the court has terminated the child’s relationship with a parent in violation of §§ 1911, 1912, or 1913, then the child, parent, or Indian custodian from whom the child was removed; the parent whose rights have been terminated; and the Indian child’s tribe each have the right to petition “any court of competent jurisdiction” to invalidate the state court’s action.181

The ICWA does not define “court of competent jurisdiction,” but the WSICWA does:

“Court of competent jurisdiction” means a federal court, or a state court that entered an order in a child custody proceeding involving an Indian child, as long as the state court had proper subject matter jurisdiction in accordance with [the WSICWA] and the laws of that state, or a tribal court that had or has exclusive or concurrent jurisdiction pursuant to 25 U.S.C. Sec. 1911.182

There is no time limitation on the parties’ right to petition a court to invalidate a state court order. In the absence of such time constraints, some state courts have sought to impose state law appeal limitations, including Washington (“No adoption which has been effective for at least two years may be invalidated under this section unless otherwise allowed by state law.”).183 This appears to be contrary to the intent of Congress.184

First, and most fundamentally, the purpose of the ICWA gives no reason to believe that Congress intended to rely on state law for the definition of a critical term; quite the contrary. It is clear from the very text of the ICWA, not to mention its legislative history and the hearings that led to its enactment, that Congress was concerned with the rights of Indian families and Indian communities vis-à-vis state authorities.185

The invalidation mechanism in the ICWA is one which provides protection to the rights of parents and Indian custodians. To petition the court for invalidation, there is no requirement that the petitioner’s rights under ICWA were violated, only that any violation under §§ 1911, 1912, or 1913 occurred during the course of the child custody proceeding.186 The types of violations, therefore, that are subject to invalidation include jurisdiction, transfer of jurisdiction, intervention, full faith and credit, notice, appointment of counsel, access to records, services and evidentiary standards for removal or termination, and consent to placement or termination.

The earliest appellate court consideration of the invocation of this provision in Washington was an adoption case in which notice had not been given to the child’s tribe. In that case, the court adopted the “existing Indian family exception” and held the ICWA not applicable even though the matter was a “child custody proceeding” involving an “Indian child.”187 This case is mentioned not for its definitive ruling on the application of § 1914, but to take the opportunity to reiterate that the Washington legislature has since acted to eliminate application of this court-created exception to application of the ICWA. In state court child custody proceedings, “if the child is an Indian child as defined under the Indian Child Welfare Act, the provisions of the act shall apply.”188 Additionally, ICWA regulations promulgated since then specifically disallow the application of the “existing Indian family” doctrine.189

Invalidation is generally mandatory where violations have occurred.190 In some instances invalidation of earlier actions has not been required where later actions have been taken by a state court in full compliance with the ICWA.191

With respect to tribal notice, technical compliance with the ICWA’s service requirements will not be required when the tribe indicates it has no interest and does not intend to intervene.192 Where tribal notice has not been given at all, or the time frames have not been strictly observed, remand to correct the notice deficiency rather than wholesale invalidation of the court’s action has been the initial remedy. In such cases, the court has held that in the absence of a tribal response to the subsequent proper notice, the trial court’s prior action would be affirmed.193

Existence of this provision is one of the most compelling reasons to ensure that all notice, procedural, and evidentiary requirements of the ICWA have been strictly complied with. Time, effort, and resources are sometimes needlessly expended only to learn that the ICWA does not apply. These expenditures pale in comparison to the disruption, distrust, and trauma that can result from unwinding actions that have been taken in violation of the ICWA. The court should inspect the notices and proof of service to ensure full compliance with the ICWA requirements whenever there is information suggesting the child might be an Indian child. The court should also make the inquiries necessary to ensure that the ICWA procedural, case service, and evidentiary standards are complied with when it has been determined that the child is an Indian child.

§12 Failed Adoption and Permanency

If an adoption decree is vacated or set aside or if adoptive parents voluntarily consent to termination of their parental rights to an Indian child, the biological parent or prior Indian custodian may petition for return of custody. The petition must be granted unless “there is a showing in a proceeding conducted in compliance with 25 U.S.C. § 1912 that return to custody of the petitioner is not in the best interest of the child.”194

This provision gives the biological parent and a prior Indian custodian standing to petition for return of the child. If an Indian child is adopted, the court must notify the child’s biological parent, Indian custodian, and the child’s Tribe when a final adoption decree has been vacated or set aside, or if the adoptive parent has voluntarily consented to the termination of his or her parental rights. A parent may waive his or her right to the notice by executing a written waiver of notice and filing with the court.195 The state agency should work with the court to ensure the notice requirements are met.196