Parent Representation in Child Welfare Proceedings

Sharea M. Moberly[1]

2024[1]

RCW 13.34 creates a statutory right to counsel for a child’s parents, guardian, or legal custodian involved in dependency or termination proceedings and provides that if such an individual is indigent, counsel shall be appointed by the court.[2] This statutory right to counsel covers all stages of the dependency and termination proceedings including hearings to establish an RCW 13.36 guardianship.[3] Washington State case law recognizes that an indigent parent’s right to counsel derives from the due process guaranties of article 1, section 3, of the Washington Constitution as well as the Fourteenth Amendment.[4] The right to counsel applies not only to indigent parents, but also to a child’s guardians or legal custodians. [5] For example, a person having legal custody of the child through a permanent or temporary nonparental custody order is a party to the dependency proceeding and, if indigent, has a right to counsel at public expense.[6]

In addition to dependency and termination of parental rights actions under RCW 13.34, state law provides for a parent’s right to counsel in certain other child welfare proceedings. Specifically, an indigent parent or alleged father has the right to a court-appointed attorney in a contested action to terminate parental rights filed under RCW 26.33.[7] In addition, indigent parents who appear in minor guardianship cases under RCW 11.130.200 also have a statutory right to appointment of an attorney where the parent objects to the guardianship when counsel is needed to ensure that consent to appointment of a guardian is informed or when the court otherwise determines the parent needs representation. [8] The right to counsel also applies to indigent parents involved in Child in Need of Services (CHINS) proceedings.[9] Also, where a non-parental custody action is inextricably linked to a dependency action due to the family court having to consider the return home of the child, the parents may be entitled to counsel at public expense because the determination whether to return the child home is considered a stage of the dependency proceeding.[10]

Indigency Screening and Appointment of Counsel

When a parent, guardian, or legal custodian appears in a dependency or any other case where the right to counsel attaches, the trial court must determine if the person is indigent and eligible for an attorney at public expense.[11] In general, a person is “indigent” if he or she (1) receives public assistance; (2) is involuntarily committed to a public mental health facility; (3) receives an annual income, after taxes, of 125 percent or less of the federal poverty level;[12] or (4) is unable to pay the “anticipated cost of counsel” because his or her available funds are insufficient to pay any amount for the retention of private counsel.[13]

Guidelines for Determining Indigency

In determining indigency, the trial court must take into consideration the indigency guidelines described in RCW 10.101, as well as the length and complexity of the proceedings, the usual and customary fees of attorneys in the community for similar matters, the availability and convertibility of any personal or real property owned, outstanding debts and liabilities, the person’s past and present financial records, earning capacity and living expenses, credit standing in the community, family independence, and any other circumstances which may impair or enhance the ability to advance or secure such attorney’s fees as would ordinarily be required to retain competent counsel.[14] The court may not deny appointment of counsel due to financial resources of the applicant’s family or friends, but the court may take into consideration the resources of the applicant’s spouse.[15]

In the context of a dependency proceeding, the screener should therefore consider that the proceeding may continue for several years and could involve a multitude of legal issues for the parent such as family law, child custody, or criminal liability issues. Additionally, the parent may be assessed for the cost of the out-of-home care and support of the child during the dependency.[16] This factor should also be taken into account when determining the parent’s ability to pay the anticipated cost of counsel. Even if a parent’s income exceeds 125 percent of the federal poverty level, the parent may be “indigent” if he or she is unable to pay the anticipated cost of counsel and cannot retain private counsel.

Indigency Screening Practices

Courts employ various procedures to screen individuals requesting public defense representation. In the majority of counties, eligibility screening is conducted directly by the judicial officer and/or a combination of judicial officer and court staff. These screeners take information regarding the applicant’s financial resources and eligibility for an attorney at public expense. In a significant number of counties the trial judge is the person who gathers this information. In many but not all counties, screeners themselves are authorized to determine if the applicant qualifies for an attorney at public expense. These employees fill out the indigency paperwork with the applicants, verify the supporting documentation, and decide whether the applicants are indigent under the statute.[17] If the screener concludes the applicant is indigent, a public defender is appointed. The Washington State Office of Public Defense (OPD) has developed an Indigency Screening Form for the courts use which may be adapted to meet the needs of each individual county.[18] In King County, screening is done by the Department of Public Defense, which also assigns counsel if the person qualifies for public defense services.[19]

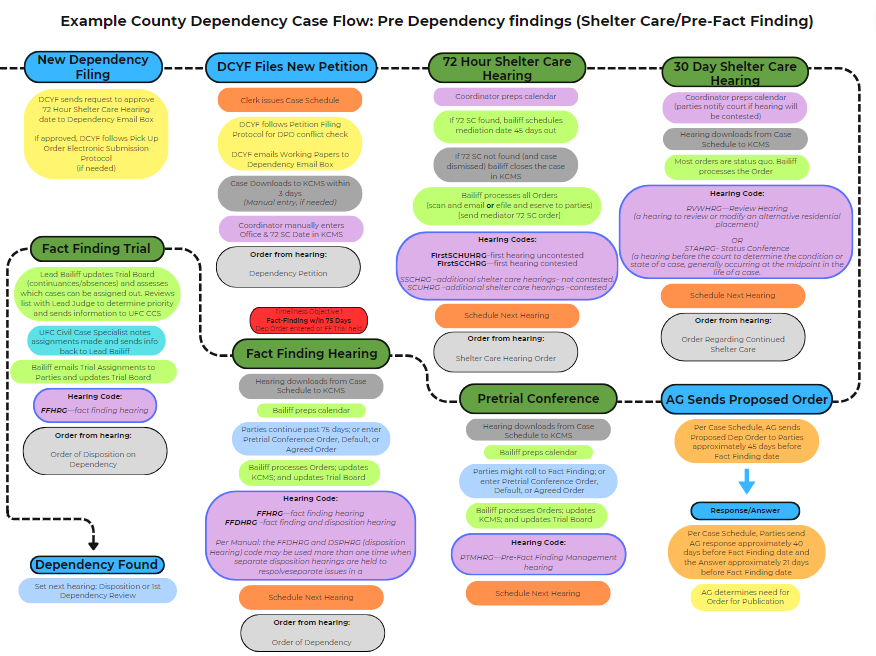

Provisional Appointment of Counsel

The determination of indigency must be made upon the person’s initial contact with the court or at the earliest time circumstances permit.[20] In a dependency action this will usually occur at the 72-hour shelter care hearing. If a determination of eligibility cannot be made before the applicant’s initial contact with the court, the statute requires immediate appointment of a provisional attorney. Thus, provisional counsel must be appointed by the time of the 72-hour shelter care hearing if the court has not yet been able to obtain sufficient information to determine indigency.[21] Local practice should ensure that public defender attorneys are present and available to provide representation at 72-hour shelter care hearings.

Indigent but Able to Contribute

The statute also provides that applicants who have some assets but not enough to pay for private counsel may be found “indigent but able to contribute” and ordered by the court to pay a portion of their defense costs.[22] These individuals may have non-liquid assets or be employed but earn less than enough to fully pay for counsel. A person who is indigent and able to contribute is defined as one “who, at any stage of a court proceeding, is unable to pay the anticipated cost of counsel for the matter before the court because his or her available funds are less than the anticipated cost of counsel but sufficient for the person to pay a portion of that cost.”[23]

If applicants are found to be indigent but able to contribute to the cost of their defense, judicial officers are authorized to order them to sign promissory notes requiring either a lump sum or periodic payments.[24]

Parents with Private Counsel and Expert Services

Extrapolating from State v. Punsalan where the court found indigent defendants who retained private counsel were still eligible for necessary expert costs at public defense, an indigent parent who has retained private counsel to represent them in the dependency or termination case may still be found by the court to be indigent for the purpose of expert costs, although this holding has not been explicitly extended to dependency, termination of parental rights, or RCW 13.36 guardianship cases.[25]

Verification of Indigency

Courts use various verification and documentation methods to investigate indigency status. The indigency statute does not require that all financial information be verified, but rather establishes that the applicant’s financial information is “subject to verification.”[26] The methods used differ depending on the size of the jurisdiction, the cost of verification versus the cost-savings that may be generated, and other county resource issues.

Indigency and the Right to Counsel on Appeal

An indigent parent’s statutory right to counsel at all stages of a dependency and/or termination of parental rights proceeding includes representation on an appeal of right as well as discretionary review, and public payment of expenses and fees necessary to provide an adequate record to the appellate court and to present the appeal.[27] Before a parent, guardian, or legal custodian is entitled to appointed counsel to assist with his or her appeal, indigency must be determined by the superior court judge.[28]

Upon filing a notice of appeal, the parent’s attorney also files a Motion and Order of Indigency and an affidavit describing the parent’s financial information, which is evaluated by the trial judge.[29] The Motion and Order of Indigency is granted if “the party seeking public funds is unable by reason of poverty to pay for all or some of the expenses of appellate review.”[30] The appellate courts, rather than the trial courts, appoint counsel for appeals.[31]

Implementing the Right to Counsel in Dependency and Termination of Parental Rights Proceedings

Before 1977, the responsibility for providing defense attorneys for indigent parents, guardians, and legal custodians was assumed by the counties. With the passage of The Juvenile Justice Act of 1977,[32] the State assumed the obligation of prosecuting dependency and termination cases, which are handled by the Washington State Office of the Attorney General. However, indigent parent representation remained the responsibility of the counties. Over the years, each county developed its own methods for appointing counsel at public expense in dependency and termination of parental rights proceedings, including county public defender agencies, contract attorneys, and panel attorney case appointments.

Attorney Qualifications

Standards of Indigent Defense adopted by the Washington State Supreme Court require that each attorney representing a client in a dependency matter meet the following requirements: satisfy the minimum requirements for practicing law; be familiar with the statutes, court rules, constitutional provisions, and case law relevant to child welfare; be familiar with any collateral consequences of a founded allegation of child abuse or neglect, establishment of dependency, and termination of parental rights; be familiar with mental health issues and be able to identify the need to obtain expert services; and complete seven hours of continuing legal education each year in courses relating to child welfare. Additionally, attorneys should be familiar with expert services and treatment resources for substance abuse. Attorneys handling termination hearings shall have six months dependency experience or have significant experience in handling complex litigation.[33]

Attorney Caseloads and Compensation

The Washington State Supreme Court recognizes a full time dependency caseload as 80 open cases.[34]

Office of Public Defense Parents Representation Program Background

A 1999 study[35] completed by the Washington State Office of Public Defense (OPD) found that payment for parent representation was inequitable from county to county and that state resources dedicated to prosecuting these cases far outpaced county funds available for parent representation. Similarly, parents lacked the case resources (such as paralegals, social workers, investigators, and expert services) that were available to the state. Based on these findings, the report recommended that Washington State fund parent representation and professional standards for representation be implemented.

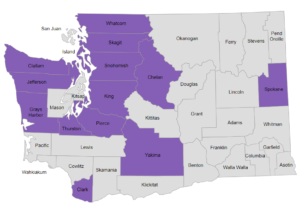

In 2000, the Legislature directed OPD to create a state-funded enhanced parent representation pilot program in the Benton-Franklin and Pierce county juvenile courts; this program has since been expanded into all 39 counties in the state. Program implementation features financial support to reduce attorney caseloads, access to independent social worker staff, expert services, periodic attorney trainings, and oversight of attorneys’ performance. OPD contracts with local attorneys to provide representation under this program. Indigency screening and case appointments are conducted at the county level.

Role of Parent’s Attorney

General Duties and Responsibilities of Parents’ Attorneys

Counsel for parents in dependency and termination of parental rights proceedings are bound by the professional and ethical duties described in the Rules of Professional Conduct (RPC). Professional standards of representation for attorneys representing parents in child welfare proceedings have been developed and describe in greater details in counsel’s role and responsibilities.[36]

In 2016, Casey Family Programs, the ABA Center on Children and the Law, and the Children’s Law Center of California brought together parents’ attorneys, children’s attorneys, and child welfare experts from around the country to discuss legal representation in child welfare cases.[37] This group launched the Family Justice Initiative (FJI) with one unified goal: to ensure every child and every parent has high-quality legal representation when child welfare courts make life-changing decisions about their families.

As a result, the FJI describes the following fundamental attributes of high-quality legal representation for children and parents. These are attributes/elements that must be met by individual parents’ attorneys as well as by the systems or structures governing legal representation for children and parents in child welfare proceedings.[38]

System attributes are needed to ensure that parents’ and children’s attorneys are properly supported to meet their individual obligations to clients. System attributes include the following:

- Appropriate caseload and compensation.

- Interdisciplinary Practice Model to ensure attorneys have access to work in an integrated manner with interpreters, experts, social workers, and investigators, and parent allies, as needed.

- Diversity and Inclusion/Cultural Humility to ensure the system provides attorney training around bias and cultural humility, including how racial, cultural, social, and economic differences may impact the attorney/client relationship, how personal and systemic bias may influence child welfare system decision making, and how attorneys can mitigate the negative impact of personal and systemic bias on clients’ case goals.

- Appointment of attorneys at case inception. To ensure attorneys provide effective representation, FJI recommends attorneys be appointed before, but at a minimum not later than, the initial appearance. Many jurisdictions provide for attorney appointment on the day of the first court hearing. If this is the case, FJI recommends the court make those appointments in the morning and schedule hearings for the afternoon to allow a more meaningful opportunity for the attorney and client to meet and discuss the allegations and case.

- Provide Support & Oversight by defining clear roles and expectations for attorneys and all members of the multidisciplinary team. Provide training and education opportunities. Provide oversight and performance evaluation. Provide the opportunity for clients to provide feedback on representation.

- Use a continuous quality improvement process to measure qualitative and quantitative outcomes.[39]

Case Conflicts

Conflicts of interest may arise in an attorney’s representation of a parent, and courts should be aware of these situations.[40] In particular, courts should avoid circumstances in which one attorney is appointed to represent both parents. In the rare case in which an attorney, after careful consideration of potential conflicts, may represent both parents, it should only be with their informed consent. The judicial officer confronted with this situation should inquire of the parents’ attorney whether pursuing one client’s objectives will adversely impact or limit the lawyer’s representation of another client and whether confidentiality may be compromised.

Even in cases in which there is no apparent conflict at the beginning of the case, conflicts may arise as the case proceeds, requiring the attorney to withdraw from representing one or both parents. In the event this occurs, the court must inquire as to whether the attorney has obtained confidential information from each client or if other circumstances exist that would require the attorney’s complete withdrawal and the appointment of new counsel for each parent.

Ineffective Assistance of Counsel

In every case, both criminal and civil, in which the right to counsel attaches, legal representation means effective representation.[41] A parent faced with the prospect of termination of parental rights to his or her child is entitled to a meaningful hearing, and that includes effective representation of counsel, as the rights at stake are both fundamental and constitutional. The appropriate test to apply for claims of ineffective assistance of counsel in dependency and termination cases has not been fully settled.[42] Appellate courts have applied both the Strickland test, used in criminal cases, and a separate due process standard.[43] Under the Strickland test, counsel’s performance must be deficient and “but for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different.”[44] Under the due process standard, counsel’s effectiveness is presumed except where the parent demonstrates that counsel’s representation deprived them of a meaningful hearing.[45]

Determining the role and responsibilities of the trial court under these circumstances can be complex, and a decision as to the court’s response in the event it believes ineffective assistance is a risk is a subject best considered with guidance from the Judicial Ethics Opinions at http://www.courts.wa.gov/programs_orgs/pos_ethics/.

Scope of Representation

Counsel for a parent is responsible for providing effective representation at each stage of the dependency or termination of parental rights proceeding. However, every event related to the dependency or termination action is not necessarily a stage of the proceeding. For example, parents do not have a right to counsel at a psychological evaluation as the evaluation is a dispositional service and not a “proceeding” or “stage” of the proceeding.[46]

Ancillary Civil Matters

A parent may also face legal matters such as housing and eviction issues, protection orders, or family court proceedings that are relevant to the dependency or termination case but clearly are not a stage of the proceeding. Civil legal aid resources are limited, and assigned counsel in dependency and termination cases often assist their clients with these ancillary matters but are not required to do so.

Agreed Nonparental Custody Actions and Agreed Parenting Plans

Parents involved in dependency proceedings often have related family law matters such as paternity actions, dissolutions, parenting plans or child support proceedings. Generally, the parent’s appointed dependency attorney does not represent the parent in these ancillary family law proceedings, as an indigent parent does not have a right to counsel at public expense in a dissolution or child custody matter.

However, in limited circumstances, state law provides a juvenile court hearing a dependency case with concurrent original jurisdiction with family court to enter agreed minor guardianships under RCW 11.130 , agreed parenting plans or agreed residential schedules.[47] Such orders must be necessary to implement a permanent plan for the child and the child’s parents must agree to entry of the order.[48] The parent’s attorney would represent the parent in these matters as they are heard by the juvenile court in the course of the dependency proceeding. When agreed parenting plans or residential schedules are entered in a dependency proceeding, the moving party is required to file the parenting plan in the corresponding dissolution or paternity proceeding in family court.[49] In many cases, this requires the parent to initiate a separate family court action. The parent’s dependency attorney would not represent the parent in the family court action.

Additionally, in the course of hearing a dependency, juvenile court may inquire into the ability of a parent to pay child support and enter an order of child support; if the parent fails to comply, a judgment may be entered against such parent.[50] In these matters that are heard by the juvenile court in the course of the dependency proceeding, the parent’s attorney would represent the parent on these issues.

Contested Parenting Plans

While the entry or modification of a parenting plan is often seen as beneficial for a dependent child, state law does not provide concurrent jurisdiction for a juvenile court to adjudicate contested child custody issues in the course of hearing a dependency. In a contested dissolution, or parenting plan that is a separate action from the dependency proceeding, a parent’s attorney may lack the time, resources, or expertise to provide representation. Moreover, such representation is beyond the scope of the right to counsel in a dependency or termination proceeding. As previously noted, an indigent parent does not have a right to counsel at public expense in a dissolution or child custody matter. In these cases, the parent’s court appointed attorney would refer the parent to a family court facilitator and or to any existing pro bono resources.

Withdrawal and Termination of Representation

Withdrawal upon Resolution of Case

Counsel should close cases and withdraw from representation in a timely manner when a final resolution of the case has been achieved and counsel’s responsibilities to the client have been completed. Whenever possible, the appointing authority should be able to access case information systems and verify that an attorney’s open and active cases are within reasonable caseload standards.

Withdrawal Prior to Resolution of Case

If, prior to resolution of the case, the circumstances necessitate counsel’s withdrawal due to a conflict of interest, counsel is required to obtain a court order allowing withdrawal and substitution of attorney. Conflicts most frequently arise when the representation of a client may be materially limited by the lawyer’s responsibilities to another client or when there is a breakdown in the attorney-client relationship. The court should inquire as to the basis for the motion for withdrawal and substitution but should be aware that the attorney may not be permitted to disclose his or her reasons for withdrawal in detail in order to preserve client confidentiality.

Where a right to counsel exists, a client does not have a right to choose a particular advocate.[51] A parent who is dissatisfied with appointed counsel must show good cause to warrant substitution of counsel, such as a conflict of interest, an irreconcilable conflict, or a complete breakdown in communication. Whether a client’s dissatisfaction with his court-appointed counsel justifies the appointment of new counsel is a matter within the trial court’s discretion, and attorney-client conflicts justify the grant of a substitution motion only when counsel and client are so at odds as to prevent presentation of an adequate defense.

Case law cited below, arising from a criminal defendant’s right to counsel, provides guidance on this issue. Before ruling on a motion to substitute counsel, the court must examine both the extent and nature of the breakdown in communication between the attorney and client and the breakdown’s effect on the client’s representation.[52] The general loss of confidence or trust alone is insufficient to substitute new counsel. The court’s inquiry must be such “as might ease the defendant’s dissatisfaction, distrust, and concern.”[53] The court’s inquiry must also provide a sufficient basis for reaching an informed decision. Factors to be considered when determining whether or not to appoint substitute counsel include the reasons given for the dissatisfaction, the court’s own evaluation of counsel, and the effect of any substitution upon the scheduled proceedings.[54]

Counsel must serve the client with the motion to withdraw and date, time, and place of the motion.[55] Ideally, the attorney should alert the appointing authority of the potential need for new counsel prior to the hearing so that the substituting attorney can be identified as soon as possible. If the motion to withdraw is granted, counsel shall take reasonable steps to protect the client’s interests and arrange for the orderly transfer of the client’s file and discovery to substituting counsel. The court should bear in mind that continuance of a fact-finding or contested hearing may be necessary when a new attorney is appointed to represent a parent in a pending case as the substituting attorney will need a reasonable amount of time to become familiar with the case history and adequately prepare for the proceeding.

Waiver and Forfeiture of Right to Counsel

There are three ways an indigent parent may waive his or her right to counsel. A parent may (1) voluntarily relinquish the right; (2) waive it by conduct; or (3) forfeit the right to counsel through “extremely dilatory conduct.”[56]

Waiver by Voluntary Relinquishment

Because RCW 13.34.090 mandates the appointment of counsel when a child’s indigent parents appear in a dependency or termination of parental rights proceeding, a waiver of the right to counsel must be expressed on the record and knowingly and voluntarily made.[57] Voluntary relinquishment of the right to counsel is usually indicated by an affirmative, verbal request and evidence of the intent to proceed pro se. For the request to be valid, the court must ensure that the parent is aware of the risks and disadvantages of self-representation and the waiver must appear on the court record.[58] Failure to create a record documenting that the waiver of counsel was knowingly and voluntarily made may result in reversal on appeal.[59] An example of questions that the court might ask inquiring into a parent’s request to waive the right to counsel is contained in Appendix C.

Waiver by Conduct

A parent may also waive their right to counsel through their conduct. Once a defendant has been warned that he will lose his attorney if he engages in dilatory tactics, any misconduct thereafter may be treated as an implied request to proceed pro se and, thus, as a waiver of the right to counsel. However, there can be no valid waiver unless the person has been previously warned of the risk of losing the right to counsel.[60] See Appendix C for a list of questions the court should ask a parent prior to determining that the parent has waived the right to counsel by their conduct.

Forfeiture of the Right to Counsel

Parents may also forfeit their right to counsel, irrespective of their knowledge of the consequences of their conduct and their intent to be represented. Forfeiture of the right to counsel lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from the voluntary relinquishment of this right because a defendant does not need to make the waiver knowingly. Consequently, a defendant’s conduct resulting in forfeiture must be more severe than conduct sufficient to warrant waiver by conduct. A defendant’s conduct must be “extremely dilatory” to result in forfeiture.[61] For example, a defendant who is abusive towards his attorney, threatens to sue him, and demands that he engage in unethical conduct may forfeit his right to counsel.[62]

In dependency and termination of parental rights proceedings, the forfeiture of the right to an attorney based on extremely dilatory conduct may also occur when a parent’s failure to attend court proceedings and communicate with his or her attorney rises to a level at which the attorney cannot effectively or ethically represent the parent’s interest.[63] However, the parent’s failure to appear for trial or last minute request for counsel necessitating a continuance does not warrant forfeiture of the right to counsel.[64] Forcing a newly appointed attorney to proceed to termination of parental rights trial without adequate opportunity to prepare a defense would result in ineffective assistance of counsel.[65]

APPENDIX A

2024 125 Percent of Guideline Table[66]

| Size of Family Unit | 125 Percent of Guideline |

| 1 | $ $15,060 |

| 2 | $20,440 |

| 3 | $25,820 |

| 4 | $31,200 |

| 5 | $36,580 |

| 6 | $41,960 |

| 7 | $47,340 |

| 8 | $52,720 |

For families/households with more than 8 persons, add $5,380 for each additional person.

APPENDIX B[67]

SAMPLE INDIGENCY SCREENING FORM

CONFIDENTIAL [Per RCW 10.101.020(3)]

Name_______________________________________________

Address____________________________________________

City State Zip

1. Place an “x” next to any of the following types of assistance you receive:

Welfare

Poverty Related Veterans’ Benefits

Food Stamps

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

SSI

Refugee Settlement Benefits

Medicaid

Aged, Blind or Disabled Assistance Program

Pregnant Women Assistance Benefits

Other – Please Describe

Recipients of public assistance are presumed indigent, but may be found able to contribute to the costs of their defense under RCW 10.101.010. State v. Hecht, 173 Wash. 2d 92 (2011).

1. Do you work or have a job? yes no. If so, take-home pay: $

Occupation: Employer’s name; phone #:

2. Do you have a spouse or state registered domestic partner who lives with you? Yes __ No<

Does she/he work? yes no

If so, take-home pay: $ Employer’s name:

3. Do you and/or your spouse or state registered domestic partner receive unemployment, Social Security, a pension, or workers’ compensation? yes no

If so, which one? Amount: $

4. Do you receive money from any other source? yes no If so, how much? $

5. Do you have children residing with you? yes no. If so, how many?

6. Including yourself, how many people in your household do you support?

7. Do you own a home? _yes no. If so, value: $ Amount owed: $

8. Do you own a vehicle(s)? ___yes ___no. If so, year(s) and model(s) of your vehicle(s):_________________________________ Amount owed: $____________

9. How much money do you have in checking/saving account(s)? $________________

10. How much money do you have in stocks, bonds, or other investments? $_____________

11.How much are your routine living expenses (rent, food, utilities, transportation) $___________

12. Other than routine living expenses such as rent, utilities, food, etc., do you have other expenses such as child support payments, court-ordered fines or medical bills, etc.? If so, describe: __________________________________________________________________

13. Do you have money available to hire a private attorney? ____yes _____no

Please read and sign the following:

I understand the court may require verification of the information provided above.

I agree to immediately report any change in my financial status to the court.

I certify under penalty of perjury under Washington State law that the above is true and correct. (Perjury is a criminal offense-see Chapter 9A.72 RCW)

_____________________________________________________________________

Signature Date

_____________________________________________________________________

City State

INQUIRY REGARDING PARENT’S WAIVER OF RIGHT TO COUNSEL

1. Do you understand that you have a statutory right to the assistance of counsel, as well as the right to represent yourself?

2. Do you understand that by having an attorney represent you, your attorney can (1) present to the court facts which may be helpful to you in this dependency and/or termination of parental rights case, such as facts about your ability to parent and care for your child(ren), the need for services, placement of your child(ren), and parent-child visits; and (2) correct any errors or mistakes in reports submitted to the court?

3. Do you understand that an attorney could advise you of potential defenses, legal strategies, court procedures, and evidentiary rules and protect your rights? Do you understand that you may not understand or be aware of these issues without the assistance of an attorney?

4. Do you understand that an attorney can advocate for you by filing motions and presenting argument on your behalf at court hearings? Do you also understand that an attorney can advocate for you outside of court and represent you during case conferences, family team decision-making meetings, and other case staffing?

5. Do you understand that if you choose to proceed without an attorney, you may not be aware of or know all of the rules governing hearings, trials, the admission of evidence, and civil procedure?

6. Do you understand that your failure to comply with the rules governing hearings, trials, the admission of evidence, and civil procedure may impair your ability to present a defense in this case and can jeopardize your rights as a parent and could even result in the termination of your parental rights?

7. Do you understand that the court will appoint an attorney to represent you if you cannot afford to hire an attorney, but you are not asking the court to appoint an attorney to represent you?

a. Do you believe that you possess the intelligence and capacity to understand and appreciate the consequences of the decision to represent yourself?

b. What is the highest level of education you have completed?

c. Can you read and understand the English language?

d. Are you physically and mentally able to represent yourself in this case?

e. Are you under the influence of any drugs, alcohol, or medication that impairs your physical or mental abilities?

f. Do you understand that you will be expected to comply with all of the rules governing every stage of a dependency and/or termination of parental rights proceeding?

8. Do you understand that the Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) has filed a petition for dependency and/or termination of parental rights and that you have the right to a trial (fact finding) to determine if DCYF can prove the allegations stated in the petition?

9. Do you understand that if counsel is appointed to represent you:

a. You cannot force your attorney to file motions, argue a position, or take action that he/she believes to be frivolous; and

b. If you continue to insist that frivolous motions be filed, frivolous positions argued, or frivolous action taken and subsequent counsel is removed from the case, then you may be required to represent yourself; and

c. Because of the multiple dangers and disadvantages involved in self-representation at a trial, the choice to represent oneself cannot be undertaken lightly?

10. Do you understand the information we have just discussed, and do you understand the risks of representing yourself?

11. Do you have any questions?

12. Do you want to speak with an attorney before you decide whether to represent yourself in this case?

13. Are you now knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently giving up your right to counsel and requesting that you be allowed to represent yourself?

ENDNOTES

[1] Written by Patrick Dowd in 2007; updated in 2011 by Amelia Watson and Brett Ballew, and in 2014 by Brett Ballew

[1] Sharea M. Moberly is a Managing Attorney with the Office of Public Defense Parent Representation Program.

[2] RCW 13.34.090(2) states: At all stages of a proceeding in which a child is alleged to be dependent, the child’s parent, guardian, or legal custodian has the right to be represented by counsel, and if indigent, to have counsel appointed for him or her by the court. Unless waived in court, counsel shall be provided to the child’s parent, guardian, or legal custodian, if such person (a) has appeared in the proceeding or requested the court to appoint counsel and (b) is financially unable to obtain counsel because of indigency.

[3] RCW 13.36.040(1)

[4] In re J.M., 130 Wn. App. 912, 921, 125 P.3d 245 (2005) (citing In re Welfare of Luscier, 84 Wn.2d 135, 138, 524 P.2d. 906 (1974)); In re Myricks, 85 Wn.2d 252, 254–55, 533 P.2d 841 (1975).

[5] RCW 13.34.090(2).

[6] See In re J.W.H., 147 Wn.2d 687, 57 P.3d 266 (2002) (Children’s aunt and uncle obtained temporary nonparental custody order prior to filing of dependency petition and were therefore caregivers with party status in the dependency proceeding).

[7] RCW 26.33.110(3)(b). But see In re the Marriage of King, 162 Wn.2d 378, 174 P.3d 659 (2007) (An indigent parent does not have a constitutional right to counsel at public expense in a dissolution/child custody proceeding as a contested parenting plan does not involve the deprivation of fundamental parental rights that would warrant full procedural due process protections.).

[8] RCW 11.130.200 states: The court must appoint an attorney to represent a parent of a minor who is the subject of a proceeding under RCW 11.130.190 where the parent has appeared

(a) The parent has appeared in the proceeding;

(b) The parent is indigent; and

(c) Any of the following is true:

(i) The parent objects to appointment of a guardian for the minor; or

(ii) The court determines that counsel is needed to ensure that consent to appointment of a guardian is informed; or

(iii) The court otherwise determines the parent needs representation.

[9] RCW 13.32.A.160(1)(b).

[10] In re E.H., 158 Wn. App. 757, 767, 243 P.3d 160 (2010).

[11] RCW 10.101.020(1).

[12] Appendix A.

[13] RCW 13.34.030(16); RCW 10.101.010 (3).

[14] See Morgan v. Rhay, 78 Wn.2d 116, 119–20, 470 P.2d 180 (1970).

[15] RCW 10.101.020(2). However, the financial resources of a spouse may not be considered if the spouse was the victim of an alleged crime committed by the applicant.

[16] RCW 13.34.160(1)

[17] RCW 10.101.020(1) states “The court or its designee shall determine whether the person is indigent pursuant to the standards set forth in this chapter.”

[18] Appendix B.

[19] King County Code 2.60.020(B)(3)

[20] RCW 10.101.020(3).

[21] RCW 10.101.020(4).

[22] RCW 10.101.010(4); RCW 10.10.020(5).

[23] . RCW 10.101.010(4)

[24] RCW 10.101.020(5).

[25] State v. Punsalan, 156 Wn.2d 875 (2006).

[26] RCW 10.101.020(6).

[27] In re Grove, 127 Wn.2d 221, 897 P.2d 1252 (1995).

[28] RAP 15.2(a), (b).

[29] RAP 15.2(b)

[30] R.A.P. 15.2(b)(1).

[31] R.A.P. 15.2.(e)

[32] RCW 13.34.

[33] JuCR 9.2 Stds., Standard 14.2(L)

[34] JuCR 9.2 Stds., Standard 3.4.

[35] Washington State Office of Pub. Def., Costs of Defense and Children’s Representation in Dependency and Termination Cases (1999), available at http://www.opd.wa.gov/Reports/DT-Reports.htm.

[36] See Washington State Office of Pub. Def., Parents Representation Standards for Attorneys (2012) available at http://www.opd.wa.gov/index.php/program/parents-representation/9-pr/99-prp-reports; and Am. Bar Ass’n, Standards of Practice for Attorneys Representing Parents in Abuse and Neglect Cases (1996) available at http://www.abanet.org/child/clp/ParentStds.pdf.

[37] https://familyjusticeinitiative.org/model/high-quality-representation/

[38] https://familyjusticeinitiative.org/model/high-quality-representation/

[39] https://familyjusticeinitiative.org/model/high-quality-representation/

[40] See RPC 1.7.

[41] RCW 10.101.005 states “The legislature finds that effective legal representation must be provided for indigent persons and persons who are indigent and able to contribute, consistent with the constitutional requirements of fairness, equal protection, and due process in all cases where the right to counsel attaches.”

[42] See, e.g., In re Welfare of J.M., 130 Wn. App. 912, 922, 125 P.3d 245 (2005); Matter of M.S.D. 8 Wn.App.2d 1023, at 3, 2019 WL 1503917 (2019) (unpublished opinion) (“Washington courts have applied two different standards to ineffective assistance claims in dependency cases.”); In re Dependency of S.M.H., 128 Wn. App. 45, 115 P.3d 990 (2005) (rejecting mother’s ineffective assistance of counsel claim under the Strickland test because she failed to show her trial counsel’s performance was deficient or prejudicial).

[43] See, e.g., In re Welfare of J.M., 130 Wn. App. 912, 922, 125 P.3d 245 (2005); Matter of M.S.D. 8 Wn.App.2d 1023, at 3, 2019 WL 1503917 (2019) (unpublished opinion); In re Dependency of S.M.H., 128 Wn. App. 45, 115 P.3d 990 (2005) (rejecting mother’s ineffective assistance of counsel claim under the Strickland test because she failed to show her trial counsel’s performance was deficient or prejudicial).

[44] In re S.M.H, 128 Wn. App 45, 48, 115 P.3d. 990 (2005), quoting Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 at 694 (1984),

[45] In re Moseley, 34 Wn.App. 179, 184, 660 P.2d 315 (1983).

[46] In re J.R.U.-S., 126 Wn. App. 786, 795-96, 110 P.3d 773 (2005); see also In re Kistenmacher, 134 Wn. App. 72, 138 P.3d 648 (2006). But see CR 35(a)(2) (“The party being examined may have a representative present at the examination, who may observe but not interfere with or obstruct the examination.”).

[47] RCW 13.04.030(3).

[48] RCW 13.34.155(1).

[49] RCW 13.34.155(3).

[50] RCW 13.34.160; RCW 13.34.161.

[51] See State v. Stenson, 132 Wn.2d 668, 733, 940 P.2d 1239 (1997).

[52] Stenson, 132 Wn.2d at .734.

[53] United States v. Adelzo-Gonzalez, 268 F.3d 772, 777 (9th Cir. 2001) (quoting United States v. Garcia, 924 F.2d 925, 926 (9th Cir. 1991)).

[54] State v. Stark, 48 Wn. App. 245, 253, 738 P.2d 684 (1987).

[55] CR 71(b).

[56] In re G.E., 116 Wn. App. 326, 334, 65 P.3d 1219 (2003) (citing City of Tacoma v. Bishop, 82 Wn. App. 850, 859, 920 P.2d 214 (1996) and United States v. Goldberg, 67 F.3d 1092, 1099–1102 (3d Cir. 1995)).

[57] In re G.E., 116 Wn. App. at 333.

[58] In re G.E., 116 Wn. App. at 334.

[59] In re G.E., 116 Wn. App. at 334.

[60] United States v. Goldberg, 67 F.3d 1092, 1102-1103 (3rd Cir. 1995).

[61] City of Tacoma v. Bishop, 82 Wn. App. 850, 859, 920 P.2d 214 (1996)

[62] United States v. McLeod, 53 F.3d 322, 325 (11th Cir. 1995).

[63] See In re E.P., 136 Wn. App. 401, 149 P.3d 440 (2006) (Mother did not consistently attend court hearings and failed to communicate with her attorney. Under the circumstances, the appellate court found that the mother’s failure to act was extremely dilatory and sufficient to justify the forfeiture of her right to counsel.); In re A.G., 93 Wn. App. 268, 968 P.2d 424 (1998) (Mother forfeited her right to counsel when she made no effort to appear for hearings, including the termination trial, and her whereabouts were unknown. She had not been in contact with her lawyer or DSHS’s Division of Child and Family Services for many months before it filed the termination action. Due to the mother’s own inaction, the court noted that the lawyer could not effectively or ethically represent her through the termination trial.).

[64] See In re V.R.R., 134 Wn. App. 573, 141 P.3d 85 (2006) (Trial court abused its discretion by denying a request for a continuance and proceeding with the termination of a father’s rights. The court of appeals held that the father did not forfeit his right to counsel by failing to appear at trial or by failing to seek an earlier appointment of counsel.).

[65] See In re V.R.R., 134 Wn. App. 573, 141 P.3d 85 (2006).

[66] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/01/17/2024-00796/annual-update-of-the-hhs-poverty-guidelines

[67] https://opd.wa.gov/cities-counties-courts/rules-and-forms-indigency-screening